How to Handle Public Speaking Mistakes

If you mess up while speaking, but don’t make it a thing, did the mistake even happen?

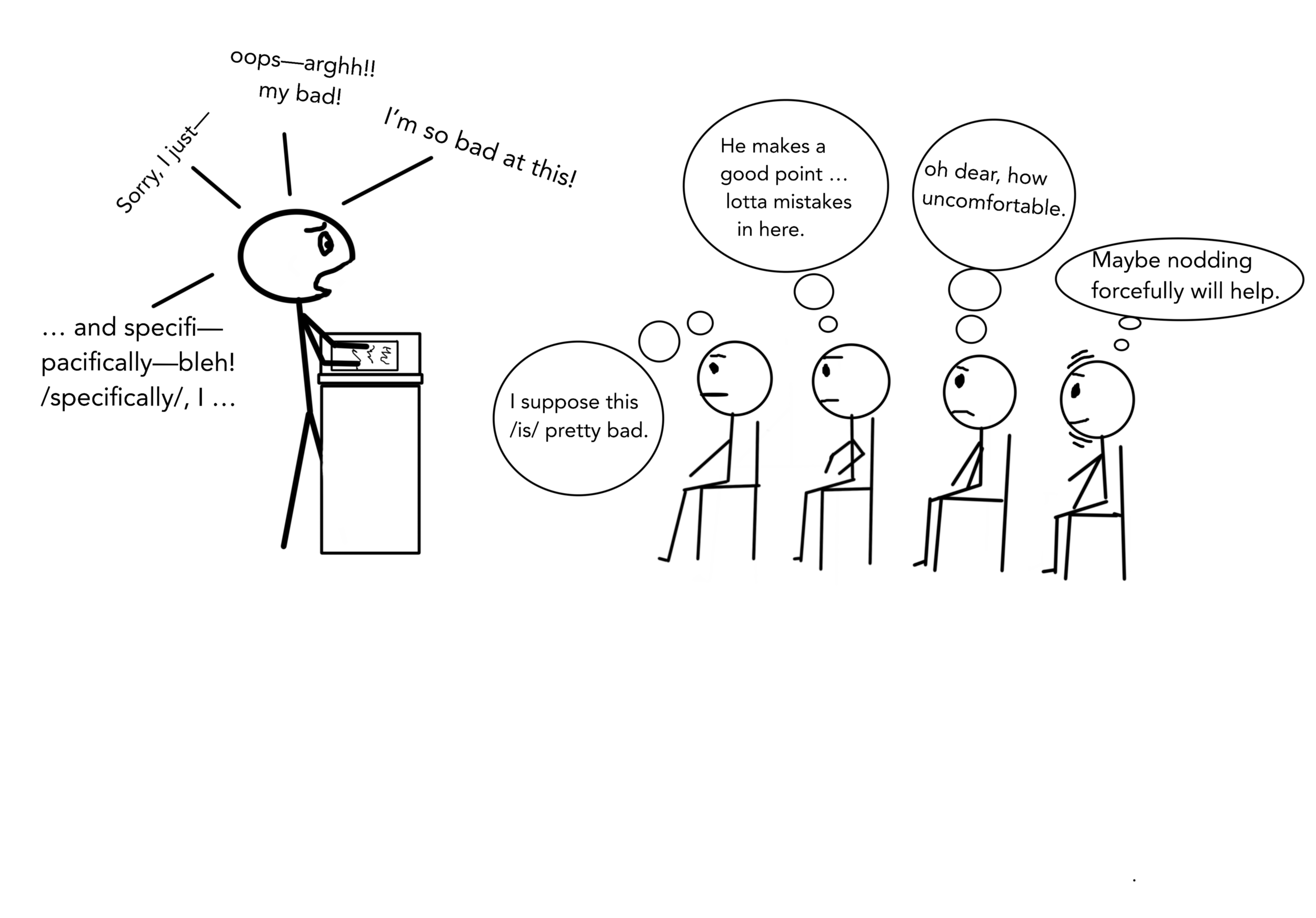

In my years of coaching, perhaps the most common trait I’ve observed in novice public speakers is this: The student stumbles through a middling but far from disastrous presentation, all while apologizing profusely for their performance. Seemingly every verbal slip-up is treated as an opportunity for an “oops—gahh!”, a “sorry!”, or an exasperated half-sigh or eye-roll. Afterwards, they offer harsh self-criticisms and bemoan their allegedly abysmal speaking skills. Tears are not unheard-of, depending on the age and nervousness level.

My feedback is usually the same: Sure, that could have been better. But apologizing made it worse. Let me explain.

Never Explain, Never Apologize

The Bank of England once had the (internal—this would not have looked great on letterhead) motto, “Never explain, never apologize.”

“It was either that or ‘Tough beans!’” (Photograph: David Levene, The Guardian)

Bad life advice maybe, but surprisingly good speaking advice! For a few reasons.

Why Apologizing Makes Everything Worse

First, most audiences are supposed to remain silent unless the speaker explicitly invites them to speak. It’s just good, established etiquette. So when a speaker apologizes, audience members are placed in the awkward position of needing to look sympathetic & encouraging, but without actually saying “oh don’t worry, go on, I’m listening.” This is uncomfortable for everyone, and expressions of Encouraging Sympathy look a lot like Pity/General Concern. Cue more nerves!

Second, audiences typically don’t notice or care about speaking mistakes nearly as much as the nervous speaker does. Apologizing, however, directs the audience’s full attention to any slip-ups. Worse, it trains them to look for those and other mistakes as you keep speaking—and what people look for, they usually find.

Third, if you effectively tell the audience that your mistakes are a Big Deal—that they mean you are a Bad Speaker and you should Feel Bad—there’s a very real danger they’ll start to believe you.

“What’s the point though, I’ve already blown it!” the distraught speaker may retort. “I’m just acknowledging what was abundantly clear to everyone!” Perhaps. But it is far more common that it wasn’t nearly so clear—and the presentation not nearly so bad—as the speaker thought. In turn, I’ve seen so many speeches from beginner presenters turn from Average to Terrible because the speaker exaggerated the severity of their mistakes, thereby letting them derail both their content and their composure.

Performative Utterances: Making It So By Saying It

There’s a concept in linguistics called “performative utterances,” in which speaking certain words performs the very act those words express. So, saying “I promise” is also the act of promising something; or when you say, “I’m gonna call this dog Woofgang Mozart,” you’re literally naming it by saying so.

Dory knows what I’m talking about (relevant timestamp: 0:22).

Pixar: Teaching advanced linguistics since 2003.

Apologies during or after presentations can function like performative utterances. By describing or implying you think your speech is awful, you may just make it so—when otherwise you’d probably have scraped by mostly unscathed.

So instead of apologizing, strive to act natural and plow ahead, keeping in mind that your public speaking mistakes likely loom far larger in your mind than the viewers’—and there is nothing to gain by shining a spotlight on them.

The Fine Print

A couple caveats & clarifications to close:

I define “apologize” broadly in this context—not just actual Sorries, but anything a speaker does to draw the audience’s attention to their mistakes. Especially when people sort of stick their tongue out and say “bleh!!” after they trip on a word. Definitely a no-no! A simple “excuse me, [correctly pronounced word]” will suffice.

Funnily enough, you can say “sorry” (or equivalent) in a speech—as long as you don’t actually look or sound apologetic. Like, a breezy “the third—sorry, the fourth point here, is (etc.)”, delivered with an unruffled air, won’t bother anyone. Exceptional speakers have these little flubs all the time. They just act chill about it and keep going—so few notice, even fewer care, and likely nobody remembers. It’s as if it never happened.

Likewise, depending on the setting, an introductory comment that (for example) your remarks might be a little scattered because you didn’t have much time to prepare, apologies in advance & I’ll do my best—this is probably fine. I mean, it still primes your audience to look for disorganization, and you don’t want to make a big thing of it or say it too often. But a brief heads-up that one’s comments won’t be super polished shouldn’t set the audience (or yourself) on edge.